January 2021, Year XIII, no. 1

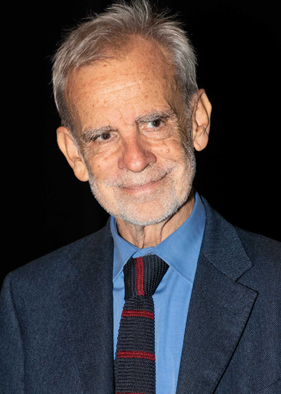

Luca Serianni

Italian: A Language without an Empire

"Italian is a language ‘without an empire’, which spread not with the strength of weapons but through the prestige of its literature, as well as its arts and music."

Telos: Dario Franceschini, Minister of Cultural Heritage, announced the creation, and funding, of the Museum of the Italian Language last August. This was like a bolt of lightening in a clear blue sky. You are the coordinator of the National Committee that is planning this museum. Could you tell us about it?

Luca Serianni: Various other languages in the world have a museum that illustrates their history and current relevance: German, French, Lithuanian, Basque... There are a total of 65 such museums scattered throughout the world.

And in 2018 the linguist Giuseppe Antonelli, who is on the committee, published a successful book with Mondadori called Il museo della lingua italiana. Of course, it won’t be a museum with a lot of stable artefacts (the handwritten texts are jealously guarded by libraries, as they should be, along with the portraits of the people who have impacted the history of the language, from Pietro Bembo to Alessandro Manzoni).

It will mostly be an interactive museum with a network structure offering several different itineraries, not merely chronological, although the various moments will be arranged according to their time in history. There will also be a fun dimension.

Visitors will be able to test their language knowledge, find out what words come from other languages, listen to how various words are pronounced in other regions, discover the etymology of many of the different food and wine specialities typical of Italian cuisine (and I’d also like people to be able to taste some of them, on a rotating basis).

It will start with the written language. It’s been said that Italian is a language “without an empire” which spread not with the strength of weapons but through the prestige of its literature – starting with Dante, who will have his own specific area – as well as its arts and music. Just think about the destiny of opera with Italian librettos: Anyone who wants to become an opera singer cannot forego learning Italian, because this would mean forgoing singing in Mozart’s Don Giovanni, in Verdi’s Traviata, in Puccini’s Tosca. But there will be more than just literary Italian. There will also be various dialects, an undeniable part of Italian history, as well as its give-and-take relationship with other world languages, paying special attention to Italian in the world: Where and why is it studied? The place chosen for the museum couldn’t be anywhere else but Florence, in a historical complex next to the Church of Santa Maria Novella.

2021 is the year of Dante, in Italy and the world. It’s been 700 years since his death, and this anniversary couldn’t come in a better year. The journey of the Divine Comedy begins in a dark wood, but step by step, within a narrative structure permeated by hope, it concludes in the glory of Paradise, a hope for salvation that we are cultivating in these dismal times of the Covid-19 pandemic. What is there for us to rediscover about Dante thanks to this celebratory occasion?

Of the many themes they’ve been announcing regarding the Dante initiatives, I hadn’t thought of the connection with the pandemic and the hope that the end of this anniversary year coincides with the end of this global tragedy: it's very interesting food for thought (and more topical than ever).

Dante is a poet who never ceases to amaze us and has admirers scattered throughout the world, not to mention that the Divine Comedy is the most translated Italian book abroad. If we think about distance, not just the temporal distance, but also the cultural and philosophical distance that separates us, we must admit that it’s extraordinary. Clearly, the strength of poetry (from individual, highly symbolic characters like Francesca da Rimini and Ulysses, to the challenge of portraying the bliss of Paradise, to the final moment of his vision of God) is capable of overcoming many obstacles. As potential opportunities to rediscover Dante, I’d mention at least three. After all, Dante isn’t just the author of the Divine Comedy. He wrote his first truly scientific-philosophical treatise, Convivio, in vernacular, not Latin. Instead, he wrote De vulgari eloquentia (On vernacular eloquence) in Latin. Here, for the first time, he describes Italy’s linguistic diversity, establishes the characteristics of eloquent vernacular and reflects on topics that today we would define as “general linguistics” (both treatises are unfinished:Evidently, to use the words of Paradise XXV, 1-2: the “sacred poem – this work so shared by heaven and by earth” urgently needed to be written. The greatness of the “lesser” Dante is well known to scholars and teachers, but maybe there’s a need of transmitting this to the greater public. What we can offer the greater public is a more in-depth analysis of lesser-known, but no-doubt fascinating cantos, if properly presented: from vividly realistic portrayals of the lower Inferno to the presence of earthly echoes not only in Purgatory, but in Paradise as well, with Beatrice’s and St Peter’s fierce tirades against the corruption of the clergy. Then, naturally, there’s the scientific work. Of the many conferences that have been announced, I’d just like to mention one that’s international in scope sponsored by the Accademia dei Lincei (next March) which will be examining Dante’s presence in world literature and extra-literary culture.

Language is constantly changing. Italian appears to have been influenced – many would say impoverished – by English words, and in particular, by the digitalisation of communication, mainly in social media. What will remain of all this in the vernacular of the near future?

There’s no question that Italian is less reactive to anglicisms than French or Spanish. Just think, to indicate that familiar device each of us uses in front of the computer, we Italians use the English word “mouse”, the French use souris and the Spanish ratón (even a computer is respectively referred to as an ordinateur and an ordenador by our cousins on the other side of the Alps). However, the relatively high number of anglicisms is not enough to “impoverish” a language. The problem, already identified by the great linguist Tullio De Mauro many years ago, is poor general education: the fact that a considerable number of adults lose what they learnt at school and find themselves using poor language and having difficulty grasping written texts that aren’t particularly complex. The institution called upon to cope with this situation, at least if we think about the young generations, can only be the school. Schools are where the foundations of education are laid and where students develop critical thinking skills, in addition to mastering their mother tongue. The plight of the pandemic and the interruption of classroom learning, especially difficult for our young cohorts, certainly don’t help. I think that’s the main problem, also in terms of language use, not the different communication methods and the linguistic habits of social networks, which actually aren’t truly pervasive phenomena, at least compared to the long time-frame in which a language articulates in its development.

LobbyNonOlet is an initiative we’ve been carrying out, for a few years now, to help people understand what representing interests is all about. “Lobby” and “Lobbyist” are commonly used words, but few people really know what they mean. They always have negative connotations, and dictionaries only seem to mention this aspect, connected to their common usage. Yet the dictionary, or better, the encyclopaedia, should also describe their true meaning and explain what it’s really all about. Do you think it’s possible to correctly express linguistically the activity of lobbying as it is carried out by professionals in the field?

Language (up to the recording of a word in dictionaries) comes after the evolution of a concept in society. In the United States, lobbying has existed for a long time: it’s accepted as a recognised practice by society and regulated by law. In Italy, that’s not how things are. When, even in Italy, its rights are recognised through a law and transparency is ensured, the respective word will also be acknowledged. However, I doubt that “lobby” and “lobbying” will work for this purpose, because, like it or not, they are words with an air of negativity that isn’t easy to dissipate. It’s better to think of creating neologism, like “representation of interests”, for instance. Perhaps LobbyNonOlet could start with this, which isn’t at all secondary: language influences how we perceive the world.

Marco Sonsini

Editorial

2021 is here at last. And it’s loaded with expectations – really loaded. It’s a very important year for the Italian language, because this year we’ll be celebrating the 700-hundred-year anniversary of Dante’s death. So who better than Luca Serianni to have as our guest for the January issue. Prof. Serianni has dedicated his entire scholarly life to the Italian language. Italian, the “language without an empire”, as defined by linguist Francesco Bruni in 2001.

After all, it was Monti, quoting Horace’s Graecia capta, who wrote that “of languages it isn’t the strength of weapons that settles disputes, but the strength of writings, repositories of human thought and of all the oracles of reason, whose strength lies mainly in words.”

In 2020 Serianni was also appointed to coordinate the work on the Museum of the Italian Language. So he talks to us about this project – the 66th museum of its kind in the world – as well as a few opportunities to rediscover Dante and Dante-related initiatives in 2021 you shouldn’t miss.

Then he reassures us as to the future of the Italian language, which he doesn’t believe risks getting overrun by anglicisms or deteriorating because of how poorly it’s used on new digital communication media.

Actually, he argues that “the linguistic habits of social networks” are not “actually phenomena that are truly pervasive, at least compared to the overall amount of time a language has been in use.” Hurray!! What he’s worried about, though, is the current plight of Italian schools – places where “the foundations of education are laid and where students develop critical thinking skills, in addition to mastering their mother tongue” – brought on by the pandemic.

People have undeniably lost touch with the Italian literary tradition of past centuries, something those who attended secondary school thirty years ago have still maintained, for better or for worse. We often hear that Dante wrote using the same language we use today, although many may find it difficult to get past all the archaic words.

Actually, though, my impression is that this is just wishful thinking. The natural break between the old and the modern happened far too quickly, and this led to the loss of more sophisticated vocabulary. Yet this is indeed the vocabulary one might happen to find in an editorial in a large newspaper, perhaps by an important journalist who also ironically uses some less common terms. This loss means that the readers are not fully capable of grasping the newspaper article in its entirety: a grave risk for a secondary school student, and even more so for an adult.

We couldn’t help engaging the prof in our battle to redeem the words “lobbyist”, “lobby” and all their derivatives. Although his answer doesn’t provide much solace, it does contain some advice, which is to work hard through our LobbyNonOlet initiative to come up with a new term to replace them, because they are “too often accompanied by an air of negativity.”

This is indeed something we’ll think about, though we’ll also keep trying to change people’s perceptions. Because, as the prof says, it is language that influences our perception of the world.

In this issue, we will also be inaugurating the new cover graphics of PRIMOPIANOSCALAc: a ripped blank page revealing part of the interview in Italian and English, with an insect looking at the words.

Insects were the source of our artistic inspiration: We find them in painting, on jewellery, on bookplates and in fairy tales. When we find them in our bed, they nearly give us a heart attack. Yet if we look at how they are portrayed, we realise they are also very beautiful. They belong to a fascinating, little-known world. Since 1999 the German Society for General and Applied Entomology has been naming an insect of the year. So someone loves them.

For Prof Serianni, we have chosen the cricket (the 2003 insect of the year). Why? Because crickets talk and make different sounds.

If one male cricket encounters another male cricket, he produces a rhythmic sound, inviting his rival to go away. If he encounters a female, he emits a faster sound that is higher-pitched but softer: a sort of whisper to court his potential partner. Then there’s Jiminy Cricket, one of the most well-known characters in Italian literature thanks to Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio and his clever use of the literary device personification.

And how can anybody who has been a student of Serianni’s forget his unforgettable university course on Collodi and his “terrible, if not cruel” tale. Those were good times!

Mariella Palazzolo

Luca Serianni

is Professor Emeritus of the History of the Italian Language at Sapienza University in Rome. He also holds honorary degrees from the universities of Valladolid and Athens and is a national member of the Accademia dei Lincei, the Accademia della Crusca and the Turin Academy of Sciences.

He is the director of the scientific magazine Studi linguistici italiani and Studi di lessicografia italiana.

Since 2010 he has been vice president of the Società Dante Alighieri. In 2017 he was appointed to be advisor to the Ministry of Education, University and Research on Italian language learning.

Before becoming a tenured professor at Sapienza University, in 1980 he was Professor of the History of the Italian Language at the Universities of Siena, L’Aquila and Messina.

Serianni is one of the foremost scholars of the Italian language and the author of several books, including Grammatica Italiana: Italiano comune e lingua letteraria (1988), and the editor of Storia della lingua italiana per immagini.

He has studied the various aspects of the linguistic history of the Italian language, from its origins to today, including sectorial language. In particular, in 2005 he wrote a book about medical language: Un treno di sintomi – I medici e le parole: percorsi linguistici nel passato e nel presente.

Some of his most recent essays include Prima lezione di storia della lingua italiana (2015), Parola (2016), Storia illustrata della lingua italiana (2017, with L. Pizzoli), Per l'italiano di ieri e di oggi(2018) and Il sentimento della lingua. Conversazione con Giuseppe Antonelli and Il verso giusto. 100 poesie italiane (2020).

He loves taking walks in the city, discovering the outskirts, cats and opera.

SocialTelos