The lobbyist profession in three points

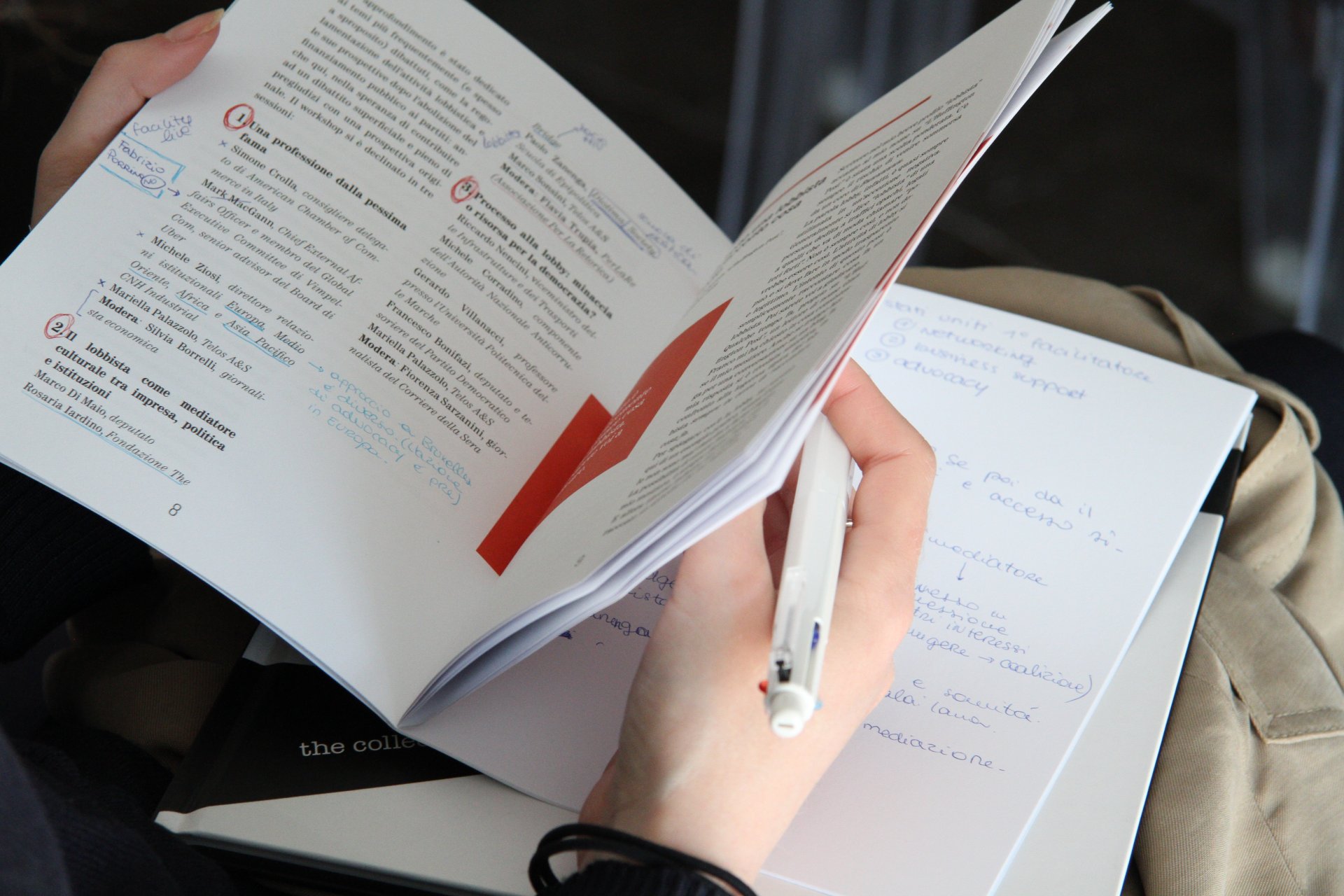

On 11 April, Telos A&S organised the workshop “Profession lobbyist: resource or embarrassing presence?” , hosted by the Salone della Giustizia in Rome. Our aim was not talking about any weighty topics, but to make three points clear. This is why we articulated our meeting into three sessions.

The first one, who is the lobbyist; the second, how does the lobbyist work; the third, regulating the profession.

One. What is the lobbyist’s role?

The first topic was dealt with in the session titled “A bad-rep profession”, attended by Simone Crolla, Managing Director at the American Chamber of Commerce in Italy; Fabrizio Porrino, SVP Global Public Affairs at FacilityLive; Michele Ziosi, Director of Institutional Relations Europe, Middle East, Africa and Asia Pacific at CNH Industrial; Mariella Palazzolo of Telos A&S. The session was moderated by Silvia Borrelli, journalist.

Our guests working in international settings such as London and Brussels were amazed that it was necessary to explain who the lobbyist was. In UK and Belgium this is a profession like any other and there would be nothing to explain. This is not the case in Italy, where this work is linked to many misunderstandings. Fixers and facilitators of different kinds are used to inappropriately define themselves as lobbyists. People promising the world, boasting about acquaintance with "the right people". We in Telos A&S do not know the "right people" because it is not what it takes for a job which requires a lot of desk work and just a few meetings aimed at making a voice heard. Without dancing around it, we would define the lobbyist as a professional expert in decision-making and his job is to help its organisation or client to present an instance. The institutions will then decide whether or not to take the proposals into account. Make a voice listened, never ask for a favour

Two. How does the lobbyist work?

The second topic was addressed in the session the lobbyist as a cultural mediator between enterprise, politics and institutions. Marco Di Maio, Member of the Lower House’s Finance Committee; Rosaria Iardino, president of The Bridge Foundation; Paolo Zanenga, President of Diotima Society; Marco Sonsini of Telos A&S. Moderated by Flavia Trupia, PerLaRe (the Association for Rhetoric).

The participants' comment was encouraging. Many have said, "We finally understood how this job works." The paradox is that the lobbyist's work is easier to do than to explain. To describe how it works, we simulated a case triggered by a concrete interest, apparently perceived only by the pharmaceutical industry (enhancing tax incentives to invest in clinical research on innovative medicines) and asked our speakers to explain which part they can play in representing that interest. It was an opportunity to clarify a fundamental aspect of our profession: the lobbyist does not only work for large companies, or for groups of companies. On the contrary, its fundamental task is to connect business instances with widespread needs and to work so that the subjects who represent them temporarily join forces for a common interest.

So the lobbyist does not work for the so-called "cartels" but for a shared instance, i.e. for a coalition of interests that may include one or more companies, other stakeholders, citizens and even the institutions. This is the case for the innovative medicines trials: in fact, the interest in their development in Italy is certainly not only a prerogative of the pharmaceutical industry, but is shared by patients and medical specialists, hospitals and the scientific research environment. For this reason, the attraction of investment in clinical research is first and foremost an opportunity for the growth and sustainability of the public health system and this is how it should be presented: not just an "interest" of more or less large groups, but a priority for health policy and, therefore, for the same institutions that set its orientations. That is the deep sense of the lobbyist's work: it is not to "put pressure" so that the institutions welcome the interests of powerful industrial or financial groups, but to build a bridge between industry interests, collective needs and policy direction, which is a precondition for effective choices for the development and well-being of the country.

Three. Regulating the profession?

Finally, the transparency issue, which has been dealt with, among others, during the session Lobby on trial: a threat or a resource for democracy?, attended by Riccardo Nencini, vice Minister of Infrastructure and Transport; Michele Corradino, a member of the National Anticorruption Authority; Gerardo Villanacci, from Università Politecnica delle Marche; Mariella Palazzolo of Telos A&S. The moderator was Fiorenza Sarzanini, journalist at Corriere della Sera. The much-debated registers are not enough. To definitively get rid of fixers and facilitators, it is important to ensure that Institutions work more transparently. “Don’t they publish everything online?” One may argue. This is not enough. Making a decision public after it is adopted is not sufficient. This is because a lobbyist is supposed to represent an interest before a decision in taken, not when all has already been done. So, it would be useful to grant to all citizens and interest groups equal and immediate access to draft regulation and preparatory works preceding policymaking (in particular, of Cabinet’s Decree and Regulations), as well as to ensure fast and certain decision-making’s timing. This would be the only way to avoid the commercialisation of information, to which facilitators promise to grant exclusive access to paying clients. Access to information relating to citizens and businesses must be granted to everyone. And here is another paradox: there is not too much lobbying in Italy, there is too little. Especially of the well-made kind.

SocialTelos